Storing data in order

Most data types have a natural order. 1 comes before 2, a comes before b etc., So you might be wondering what’s the big deal about keeping things in order but when we are storing them in btree (or some sorted container) bunch of interesting details emerge in doing this efficiently. Database management system typically takes care of this, user simply defines the data types for each column and indicates which column(s) form the primary key for the table. This is used to store rows in the order defined by primary key so that later it can be searched efficiently to find what user is looking for.

Core part of this is the comparison function that is used to decide the order of data. For a database to be useful it needs to support a variety of data types and allow composite primary keys that mix these data types in arbitrary order. Naively we can implement the comparison function by leveraging the schema to materialize the data first and then attempt comparison. For example if id is defined as integer then we can read the bytes into integer variable and compare those. But materialization is expensive and speciality comparison code like this can lead to poor performance.

An alternate way to do this is to define a generic lexicographic comparison function over byte arrays and store the data in such a way that the lexicographic order is identical to natural order. This makes our comparison function really simple and efficient. For a real world example, you can refer to the rocksdb cursor interface which stores key/value as byte arrays 1. Say we are building a relational database using such a tree implementation, we need to map table rows to byte arrays while preserving the order. Lets take a look to see how we can implement such a mapping.

Lexicographic order

Lexicographic order (alternatively called dictionary order) simply means data is alphabetically ordered 2. As humans we can pattern match and understand that ‘a’ comes before ‘b’, ‘b’ comes before ‘c’ and so on. But how do we codify this so that computers can understand this?

Lets simplify this to assume that our alphabet has only two symbols, 0 and 1. And the order is defined as 0 comes before 1. Using an example where we have two sequences, say 100 and 101. There are 2 rules to sort this data,

- We will compare character by character, if they match then we continue to next character otherwise whichever sequence has smaller value comes before the other sequence in lexicographic order.

- If we run out of characters in one of the sequences, then the sequence that is shorter comes before the other sequence.

It is fairly straightforward to extend this to bytes and that is basically what memcmp does. Some databases further optimize this comparison function with architecture specific instructions to improve performance, for example take a look at lex compare used by Wiredtiger.

Now that we have our comparison function, lets look into packing bytes for various primitive types in such a way that it yields the correct order.

Strings

Strings are great because all we really need to do is give some byte value to each character in our alphabet in dictionary order. One such encoding is ASCII encoding of characters where we assign a byte sequence to alphabet such that if follows the same order (A is 65, B is 66, so on). So using some character encoding we can translate the string to bytes and voila our comparison function just works.

Fig 1: ASCII table

A single byte works well for english alphabet but once we start supporting other languages we need more unique values. Smart folks at Unicode already did this and defined UTF-8 encoding that we can use (it is also backwards compatible with ASCII encoding).

In practice this is a bit more complicated where we have to deal with lower case/upper case, accents/umlauts in languages like German, complicated gylphs in eastern languages. Database management systems typically let the user specify collation to precisely control this (some set of rules that define the ordering of letters). Collation is outside the scope of this article but refer to Mysql or Postgres for an excellent introduction to this topic.

Integers

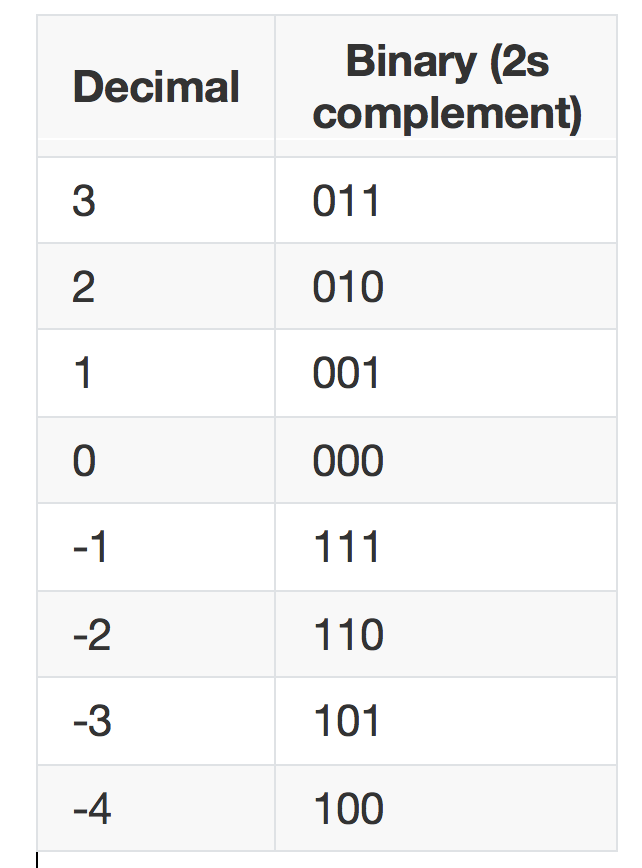

Now onto some interesting stuff. Integers are generally represented in 2’s complement notation which greatly simplifies implementation of arithmetic operators but makes lex comparisons a bit harder. Say we have a 3-bit integer,

Fig 2: Binary representation for 3-bit integers

So if we only consider positive integers lex compare just works. But for negative numbers it gives incorrect order, -1 is considered the largest number here and any negative number is larger than positive ones. This is a problem because if user asks to return all data is that larger than 4 we will incorrectly return -1. So how do we fix this? We fix this by mapping from signed space into equivalent unsigned space.

Hopefully you can see it, the mapping is just adding the negative of smallest value that can be represented. So -4 becomes (-4 + 4) = 0. In practice this is a bit tricky since 4 is not representable in 3-bit integer space but the effect of above transform is that only the sign bit is flipped. Equivalent operation can also be achieved by XORing the binary representation with the smallest value (100 ^ 100 = 000).

let min: i32 = std::i32::MIN;

let res = x ^ min;

return res.to_be_bytes()

Once we map to unsigned int space we can just use our lex compare function and its order is same as natural order of numbers. We can extend the same transform for larger integer sizes (short, int, long).

Another thing to note here is that lex compare works by moving from most significant to least significant which means we need to store the data in big endian format. This is not a problem but it does waste a bit of space because of all the leading zeros for small values. A simple algorithm to save space here is to use variable integer representation, strip the leading zeros and write the length ahead of the data (recursively invoke the function to convert length to bytes). There are of course faster implementations for this such as varint implementation from Wiredtiger, intpack.i 3

Decimals

Decimals are even trickier compared to integers. We will constrain ourselves to approximate ones here such as float and double that are commonly represented using IEEE-754 standard.

Fig 3: Single precision float

Interestingly IEEE-754 representation uses a similar trick that we discussed above in representing the exponent, that is signed exponent is shifted by an offset to make comparisons work (this is called exponent bias). Since exponent is leading and usually denotes the magnitude of the number, byte order is identical to natural order for positive values. For negative values this needs to be in the reverse direction i.e., larger the exponent, smaller the number (similarily for fraction too).

If we simply interpret the bytes as 2’s complement signed integer representation, we are mostly there except that the order is wrong on negative side. To fix this subtract all the negative values from the smallest value (after intepreting the bytes as signed 2’s complement), this fixes the order and also guarantees that the values are still negative 4. Once we have the data in 2’s complement order we can simply flip the sign bit to order positive and negative values.

let min: i32 = std::i32::MIN;

let mut res = unsafe { mem::transmute::<f32, i32>(x) };

if res < 0 {

res = min - res;

}

res = x ^ min;

return res.to_be_bytes()

Composite keys

Now that we have bunch of primitive types correctly ordered, lets look at cases where we have composite keys. We need to pack bytes for these columns in such a way that the lex order is equivalent to the order obtained by comparing column at a time 5. Taking it step by step,

Fixed size columns

If we are dealing with only fixed size columns, then simply concatenting the bytes just works. This is because larger key comparison simply translates to individual column comparisons in the order defined by the user.

Variable size columns

Say our composite is two string columns ("a" "ab" and "aa" "b"), simply concatenting them yields ambiguous order whereas if we individually compare the columns they do have a well defined order.

Now there is a really simple way to fix this, so simple that it always blows my mind that it actually works. All we have to do is append a zero byte at the end of the string. Since zero byte has the lowest byte value compared to any character, we are guaranteed to end our comparison when we start comparing it with the next string.

This is great because it is essentially how strings are stored in C so you can even directly use the address of the underlying string. Additionally the zero byte also eliminates the need to store lengths of variable size strings as it can be used to identify the column boundaries.

Mixed types

Mixed types are when we have columns that are of different types. This again simply just works because we already guaranteed that non-string data types are lex comparable, which makes this just a subset of variable sized columns where one column always happens to be of same size.

So supporting composite keys is actually very straightforward, just concatanating bytes of each column as long as we can guarantee that the each column’s lex order is same as its natural order.

Summary

Using these transforms we can store any arbitrary schema defined by user in our key/value store (say RocksDB), users can define the schema which we can translate to a simple key & value byte arrays. Query engine can then issue full or partial key searches to find the position in the tree quickly and traverse from there, which is roughly how indices work in a database at high level (row-wise storage) 6.

Hopefully this has not been a complete waste of your time and you found this useful. If you have any comments/feedback, you can reach out to me @sainathmallidi

-

RocksDB does allow user to define a custom comparator but in rest of this article we primarily look at how to represent information in such a way that default comparison function just works. ↩

-

Alphabet really here is just any arbitrary sequence of symbols with a well defined order. ↩

-

Equivalent rust implementation: rust-varint ↩

-

How did this work? Lets use a small 3-bit integer space to illustrate this. Say we have negative numbers [-1, -2, -3, -4]. To reverse the order we can subtract them from zero which successfully flips the order [1, 2, 3, 4]. Problem is that this also modified the sign bit and since we actually do have positive values this interferes with that. Rather another way to do this is to subtract the values from the smallest value (-4). Now the order is [-3, -2, -1, 0] which is also the reverse of the original order 7. ↩

-

This is kinda similar to the original lexicographic compare function defined except that each symbol is now a arbitrary long byte array. ↩

-

In this article, we have not merged data spaces together. Which means if we have variant columns where it can take either int or float value, our ordering functions dont really work. There are some interesting techniques to define a total order across types, here’s one such idea from Peter Seymour - Efficient Lexicographic Encoding of Numbers. ↩

-

If you noticed that one of the negative numbers mapped to 0 here which is already a valid position. Luckily IEEE-754 has both positive and negative zeros so we effectively mapped both of them to same byte sequence, this works nicely for comparison code

-0 == 0. At the same time this is lossy as we cannot reconstruct zero correctly if we need to preserve the sign bit. ↩